Despite being located in the second smallest district in Lima, Barranco’s hidden gem is unbeknownst to many. Have you seen this hillside ‘elevator’?

Ask a visitor—or a resident, come to that—what’s worth visiting in Barranco, the quirky Bohemian suburb of Lima, and they’ll probably say something about the Puente de los Suspiros, the plaza Municipal de Barranco, or perhaps one of its fine restaurants.

As a resident of the district for the past four years, my list would not be complete without mention of one of Barranco’s hidden gems: the remains of the once glorious funicular railway. This railway once ran up and down from the end of Calle Domeyer to the beach below.

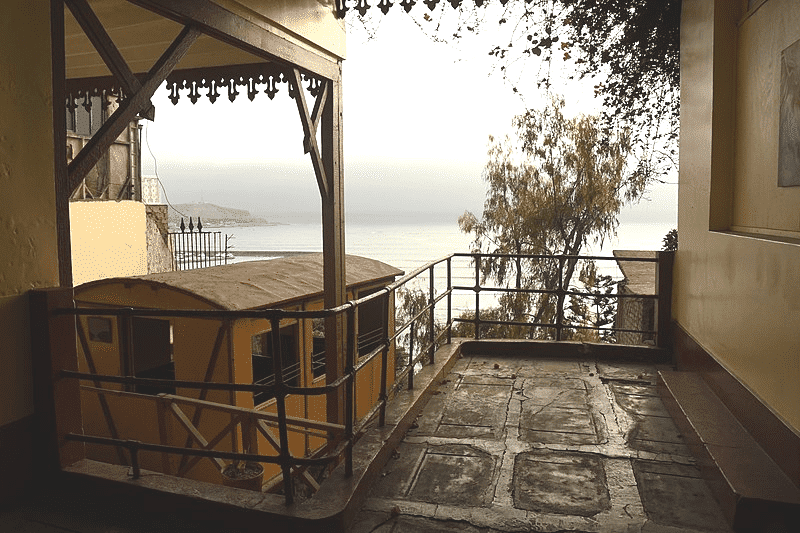

And hidden it is. Parallel to the old lglesia la Ermita is Calle Domeyer, a street named after a notable German resident of Barranco who played a leading role in the building of the funicular. Walk to the end of this charming street and you’ll see two sets of iron gates, the first leads you into where the old funicular station was situated on the left. To the right is Domeyer’s gothic mansion, now home to the notable Peruvian artist Victor Delfin.

Take a few steps towards the second set of railings and you’ll be afforded a fine view of the ocean. The remains of the funicular passenger car, to the left, are perched outside the top station as if about to make its final descent.

The rise and fall, as it were, of this extraordinary form of transport, tells us a lot about the history of Barranco and even Chorrillos, the neighboring district which had Peru’s first (and only other) funicular.

There is something fantastical about a funicular. From the Latin for rope, a funicular seems designed to defy gravity, a legacy of the days when adventurous travel (albeit for a few minutes) wasn’t a thing of the past.

Barranco’s particular funicular opened on July 28, 1896. It was the brainchild of two German residents, Rudolf Holting and his friend Domeyer. Funiculars were very much a feature of the late 19th century when innovations in engineering and railway design solved the problems of transporting people and goods up and down steep inclines. Valparaiso in Chile, for example, had thirty funiculars of which sixteen remain.

Before the coming of electricity, Barranco’s funicular operated by means of the filling and emptying of tanks of filtered sea water which hydraulically allowed two cars to go up and down simultaneously. These water tanks were built under the floor of each car which were filled or emptied until just enough imbalance was achieved to allow movement. The car at the top of the hill was loaded with water until it was heavier than the car at the bottom, causing it to descend the hill and in so doing pulling the other car up. The water was drained off at the bottom, and the process repeated with the cars exchanging roles. The movement was usually controlled by a brakeman.

Barranco’s funicular passenger cars were built of Canadian pine and each car could hold about 28 passengers. Rides would depart every 30 minutes and were signaled by a bell rung by Rudolf Holting. A glance at the photograph above reminds us there was no Pan American Highway at this time, so the funicular was able to arrive straight onto the beach where it was possible to bathe in one of the long-gone baths.

On February 9, 1930, the Barranco funicular was electrified as a single double-capacity car which gave it a further lease of life. Unfortunately, the cost of repairs, the removal of the baths, one or two accidents, and the advent of the motor car hastened its final journey in 1971.

There has been talk over the years of investment to bring it back to its former glory. In 2014, there was a suggestion that the funicular would be renovated by the Ministry of Housing at a cost of S/ 5 million as part of the cable cars program. But like the funicular, such plans go up and down.

But if the idea of a funicular is sleeping in Barranco, it is still very much awake elsewhere.

Two years ago, the Swiss inaugurated the world’s steepest railway, the €44.6m Euro Schwyz-Stoos funicular. It has since been hailed as a triumph of modern design engineering. A level-adjusting function allows space-age-looking carriages, accessible to all users, to remain horizontal while speeding up a 1,720-meter track at 10 meters a second with gradients as steep as 110%.

Rudolf Holting and his Barranco neighbour, Domeyer, would be proud.

David Stephens is a writer and founder of the Lima Writers’ Group. He lives in Barranco and is currently working on his second novel, Acts of Disappearance, set in Peru.

Cover photo: Web Noticias Libre de Peru/Andina